I’ve talked about which qualities I look for in a company. If it was just a matter of finding the qualities we like in a company, life would be easy – we’d buy shares in Apple and Google and Costco and ignore the market. And heck, there are people who do that. A stock represents a company, so when we buy a stock, why not buy the best?

It’s important to remember, though, that you have to pay a price for a stock, and that price matters. Microsoft offers the classic example – if you bought Microsoft at its December 1999, when it was a great company with a dominant position and a decent bit of control over its future, you would have had to wait nearly 16 years for shares to break even, or 14.5 years if you include dividends. This despite revenue growing over 9% a year, a solid number.

With that in mind, here’s what I look for in a stock so that I can protect myself against a Microsoft situation.

Attractive valuation

Price matters. Unless I’m really sure that the company I’m investing in is going to grow faster than what the market expects or even what I expect, I want to pay less for the company than I think it’s worth.

How do we know what a stock is worth? That’s a subjective argument. We’ll spend a whole course on how to value stocks so we have the tools to answer it as well as we can.

The short answers are ‘some multiple of how much money it will make’ or ‘all the money it will make in the future, discounted back to today.’

Let’s assume we have those answers. The company historically trades at 23x earnings, and we think that’s a fair number. Or the S&P 500 trades at 21x earnings, and we think our company should have the same multiple, because it’s as good a company as the average S&P 500 company. That’s the ‘value’ in our view.

I think an attractive valuation is a share price something like 33% below our estimate of value. Or in other words, we should have 50% upside to fair value.

I don’t mean to be overly precise. 50% is just a starting point to think about. Some investments have a higher degree of certainty but a lower degree of return, or vice versa. Your choice of a discount might be different, or you might think about buying something for less than it’s worth. But I like to start with a thought that there is a chance to return 50%, in my normal investment.

I’ve said I’m a value investor, and a growth investor might look at this as crazy. But I think you can use the same concept for growth investing. You just have more confidence that the company will outgrow expectations, which gets you to a worth in the future that is higher than the current price.

Reasonable relative valuation

Valuation in a vacuum can be tough to establish. We can estimate how much money the company will make in the future, apply some math to get an estimate of how much that money is worth now, and stop there. That might be a pure estimate, but it’s also a little naïve if we don’t look around.

There are three things we can compare the company’s valuation to, so we understand better whether this is a good time to buy.

Peer valuation

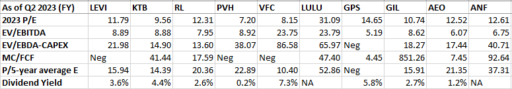

How does the company’s stock compare to peers? Here’s an example snippet from a spreadsheet I have looking at Levi Strauss, a stock that I have bought a small amount of shares in.

As of September 28th

What’s going on there? These show a few ways to value a company – price to earnings, enterprise value to EBITDA, Market cap to free cash flow, and more. We’ll go into them later.

When I started out investing, I assumed that this was a math problem. Pick the company with the lowest numbers (except dividend yield, which you would want to be high), and invest in that. Investing doesn’t work that way. The companies that are ‘cheaper’ are cheaper for a reason.

Now, I use this more to check how attractive the in a vacuum value is. If Levi Strauss seems really cheap on a PE basis, does that reflect that the whole apparel industry (except lululemon) is cheap? If so, what’s going on? Trying to answer that question is why I haven’t bought many shares, yet.

Market valuation

This is a simple one. Compare the valuation of your stock to the S&P 500. The S&P 500’s PE should represent the ‘average’ valuation for the biggest companies in the market. If you have a ‘good’ company, it might deserve an above-market multiple. If it is an average or mediocre company, maybe you don’t make that argument.

A very, very loose rule of thumb that I keep in my head is that a 15-20x PE multiple is an average, fair price. 10-15 is starting to get interesting, and below 10 is cheap, though watch out for reasons. 20 and above is getting pricy, but maybe the company is good enough to deserve it? The S&P 500 is trading between a 20 and 25 multiple, depending on whether you look backwards or forwards*.

*Backwards is often for the prior twelve months, notated as TTM (trailing twelve months) or LTM (last twelve months). Forwards is for the next twelve months (NTM) or the next fiscal year (2024 earnings at this point). Forwards multiples are usually lower than trailing multiples, as company earnings usually grow.

One note here: the S&P 500 valuation is skewed by Apple, Microsoft, Google, etc. These are some of the biggest and best companies in the world, with high PE ratios. It might be inappropriate to compare a local bank or small industrial company to the S&P 500.

Historic valuation

You can look at how your stock has traded in the past to get an idea of how it might trade in the future. If a stock normally trades at 9.5x earnings and is now at 6.2x earnings, you can:

a) assume something’s going wrong, and

b) argue that when that is solved, the stock should return to 9.5x earnings.

There’s no guarantee you’ll be right. You have to understand what earnings will be after the problem is solved. But, it’s at least a reasonable basis for a valuation argument.

Understand the disconnect

Underlying all of these points about valuation is that you want a disconnect between price and value. But why is there this disconnect?

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) argues that there is never a disconnect. The share price today reflects all available information, and if a stock moves it’s only because new information became available, and it will be priced in immediately.

Even in this statement, we can see a flaw – it’s possible to anticipate information about a company’s earnings or prospects. That said, I also think EMH, in its purest form, is silly. People are trading stocks, even if they program computers, and that causes irrational swings and thus opportunities.

At the same time, we shouldn’t be overconfident or foolish. Just because Levi Strauss trades below the market multiple doesn’t mean the market is pricing it incorrectly. We have to figure out why Levi Strauss is cheap. Does it have too much inventory it’s going to have to sell off for cheap? Or is it not growing? Or are there concerns over management? Whatever the case may be, there’s often a reason.

Examples of a Disconnect

Here’s a couple examples from my investing this year: I bought shares in Steelcase, an office furniture maker. The reason its shares are cheap is pretty obvious – work from home has persisted longer than expected, and may have permanently damaged office furniture companies. There is data to support that and more depth to the story, but that’s the reason, and it’s a good one. My argument for buying shares has to incorporate and/or refute that reason. I say that the shares are cheap enough that I don’t need a return to 2019. I just need more office activity in three years than there is now. That feels like a better bet, though we’ll see how it plays out.

Source: Steelcase

Here’s a special situation: National Instruments Technology (NATI) sold itself to Emerson Electric this year for $60/share. Emerson came public in January with a bid of $53/share, and NATI said, essentially, “let us see what’s out there.” Shares were trading just under $53 when I started buying. It seemed obvious to me that if NATI couldn’t find a better deal they would take $53. Reports suggested there were other suitors. And then things went quiet for a few weeks, and shares drifted all the way down to $49. I couldn’t understand why the market lost faith in the situation, and so I only built a 1% position.

Perhaps instead, I should have realized that there was no great reason, and gone bigger. In any case, the news broke in April that Emerson had won the bidding at $60/share. Not fully understanding the disconnect, or not recognizing how well I understood it, cost me a chance to make a good deal of money.

Risk Reward

The risk vs. reward in a stock is another vital factor. As Joel Greenblatt, a famous mutual fund manager and author, writes, the key is to “look down, not up” when you invest.

The risk is how much money you might lose if you’re wrong in your argument. For Steelcase, if they don’t improve from last year, I can be confident it still won’t go bankrupt: free cash flow was positive, and earnings were positive, and the balance sheet is ok if not amazing. So that’s off the table.

It earned $.30 / share last year. If it does that again for two years, maybe the market prices that at 12-15x earnings, because it’s starting to lose hope Steelcase will return to its $1 / share pre-pandemic earnings levels. My downside is $3.60-$4.50/share, vs. the $7.36 average price I have in my portfolios. About 50% downside. I think that’s a fair worst-case scenario.

For that to be worth it, I have to believe that it’s unlikely to come to that, and/or that the upside is much better. If Steelcase delivers on its management day projections, I estimate it will make $1.17 / share for the year ending March 2026. By that point if it’s growing well, a 15x multiple would be a little less than what it averaged in 2018-2019. $17.55 is the upside, or 138% over the next three years.

I may be wrong, I may be right. If I did decent work and get to the point where I have a reward that is two or three times more than the risk, that is attractive. If I can argue the bull case is more likely than the bear case, then it’s even stronger. Whether I’m right in this case is irrelevant*, though: the framework is what I’m getting at for risk vs. reward.

*except to me/my investors

Margin of Safety

Benjamin Graham, the father of modern value investing and Warren Buffett’s mentor, is best known for two concepts. Mr. Market, which I covered here. And margin of safety.

Source: Wikipedia

What is margin of safety? “The discount at which the stock is selling below its minimum intrinsic value, as measured by the analyst.” Which encompasses the point I made about attractive valuation. Attractive valuation is informed by our understanding of relative valuation and the disconnect between intrinsic value and the stock’s discounted price. Risk/reward is a last piece for checking that I’m safe not only in my guess of the opportunity, but in case things go wrong.

Margin of safety underlines the principles here, but I’ve always viewed it as a little bit of a truism. Look at the statement again: “The discount at which the stock is selling below its minimum intrinsic value, as measured by the analyst.” See that last phrase*?

*I should hope so, I bolded it.

All of this work we’re doing is based on our own analytical abilities and estimates. As hard as I might work to check for all of these factors, as well as what I mentioned about finding good companies, there’s no promise that I get it right. If I misunderstand, if I get poor information, if I analyze wrongly, or if bad stuff just happens, I could lose money.

Margin of safety in and of itself, then, is meaningless. But, thinking this way is a good way to prepare yourself for getting things wrong, or for bad things happening. I view a margin of safety as a way to protect myself when I’m wrong, by demanding stocks that are not priced to perfection or overly risky.

The marriage of stock and company

I’m looking for companies of good quality, and stocks of good price. When those two cross, boom, I have a good stock to buy. When there’s only one or the other, we get on a spectrum, and the decision gets harder. There will be cases where I lean more on the price in my reasoning, and cases where I lean more on the business*.

*Special situations like NATI are their own can of worms, to be covered in a post or two later.

These are the four things I’m looking for from the stock. When I get as many of these things as I can, along with as many of the ‘good company’ checkmarks as I can, I have a good buying opportunity. And while it may be hard to find companies and stocks that pass a lot of these factors, we don’t have to buy that many stocks. Buy 6 stocks well, get 3 sort of right, 1 really right, and 2 wrong, and you probably have a good portfolio. As Buffett says, wait for those fat pitches, and then be ready to swing.

Practicing my swinging motion.

In my next post I’ll go back into the mechanics of how to swing: the ins and outs of actually buying a stock and the feelings that come with it.

Disclosure: I own positions in Steelcase, Levi Strauss, and Apple.

One response to “4 Must-Have Qualities I look for in a Stock”

[…] all the work on finding a stock idea, studying a stock, deciding what you like in a company and in a stock. Now you need to know how to buy a stock. Should be easy, right? Well, not so […]