Remember newspapers? When’s the last time you held and read a newspaper?

I’ve loved and read newspapers almost as long as anything else in my life. There was one part of the newspapers I never quite dove into as a kid, though: the business section, and specifically the tables of stocks. Columns and columns of ticker symbols and numbers stacked on top of each other, with their own language that is indecipherable at first glance, but that hold great import, more than the baseball box scores or comics panels I was more comfortable reading – well, maybe not more than Calvin and Hobbes. Still. Having learned this language, when I am in the U.S. in the summer, I borrow my father-in-law’s copies of Barron’s, mostly because I like to look over the tables.

Most people don’t read newspapers, which is a shame but its own separate topic. And I don’t know if people ever actually used the newspaper stock tables, or if it was more to check up on prices, or what. But there’s a modern way to scan the world of stocks to find investing ideas: stock screeners. They offer you an easy way to narrow down the pool of potential stocks and pick from only the ones that suit your criteria. As with any method, there are limits, but it’s a good tool to have in your toolbox. This post will explain how to use stock screeners to find stocks for your watch list.

What is a stock screener?

A screener is a filter, a way to monitor and sort through what you want from what you don’t. A luggage screener filters out the safe suitcases from the ones that might be dangerous; a window screen lets in the air but filters out the bugs (at least, hopefully). A stock screener filters out stocks that wouldn’t interest you at all, so you can find a more interesting list of stocks to research and potentially buy.

Get A Short Investing Guide in your inbox

Where do I find a stock screener?

Most brokerages will offer stock screeners. It might be filled with pet products or strategies, but the brokerage’s screener will offer the basics – the size of a company, how much debt or cash it has, how much money it makes, the price of the stock compared to how much money it makes, what industry or sector it is in, and so on.

Your brokerage stock screeners will probably be good enough, but there are tons of screeners available on the web if you want to go farther. I’m not going to review all of them, but you can find a couple sites that compile reviews of stock screeners. I use Investing.com’s Pro screener, from my last job, as I like its international angle and how well it integrates the fundamental characteristics I want to search by. But there’s not a ton of magic – you just need to make sure it’s a credible source so the data is correct.

How do I use a stock screener?

I’ll provide a sample process for how to use a stock screener, using Fidelity’s screener (in the video above, I show this on my screen using TDAmeritrade).

You’ll see a screener might start with some pre-set options. Beyond what’s here, you might just look for recent 52-week highs – companies whose stock reached their highest point in a year – or recent 52-week lows. Recent IPOs can be fun to look at*.

*All three of the “recent” lists would be in a weekly Barron’s or even the daily newspaper stock tables.

Those are fine to play around with, but remember – part of what we’re trying to do is find something other people haven’t found yet. It’s better to find our own criteria.

If you’re watching this as a new investor, you may have no idea where to start. I’ll go into what I look for when buying a stock later. Your investing style will also affect how you screen. But let’s use one set of criteria just to start.

Our sample stock screen

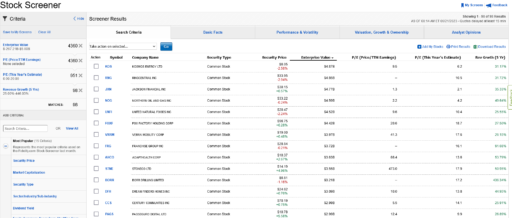

Let’s say I don’t want a huge company. I filter by companies with an enterprise value under $25B.

Then I want to find companies making money but that are not super expensive. I select price to earnings (PE) ratio for the trailing twelve months (TTM) above 0, so this is only profitable companies. Then I add PE ratio for this year’s estimate of 0 to 20 – still only profitable companies, but now I’m cutting off some of the more expensive ones.

Lastly, I filter for companies that have grown revenue (i.e. sales) at least 25% in the last 5 years.

Our screening criteria, then are:

- Enterprise value < $25B

- PE Ratio TTM > 0

- 20 > PE Ratio this year’s estimate > 0

- Revenue growth last 5 years > 25%

That’s narrowed us down from thousands of stocks to 4360 to 951 to 98 stocks which represent companies that are not huge, that are profitable, and that have grown revenue over the last 5 years. 98 is a manageable number to choose from when I want to start researching.

I want to stress: this is just a sample set of criteria to illustrate the process and not anything you should plug into your screener right away. I want to show how screeners work in general, not share a screening idea.

What do I do after I have a list of stocks?

Now what?

Remember that a stock screen, like a Peter Lynch style insight or any stockpicking method, is just a starting point. You should not buy a stock just because it shows up on a list. Instead, you can start researching it.

If we go back to our list, for example, there’s a company whose ticker symbol is DINO. Maybe you think that’s funny. What’s its deal? Well, you can click on it to see its stock page, you can add it to a watchlist, or you can google it and start learning about it. This is just a way to narrow down from all the thousands of stocks you might consider to a smaller list that, at least in theory, could be more interesting. We’re still a couple steps from buying, and we haven’t even developed our best screens yet, but when you’re learning, it’s worth starting anywhere.

Limits to stock screeners

Beyond that important limitation – that stock screeners can only produce statistical information and not enough to tell you if a stock is worth buying – there are a few other issues to watch out for.

Data fidelity

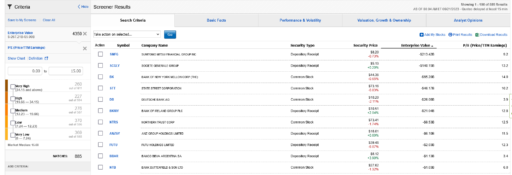

A screener is only as good as its data, and sometimes its data is set up wrong. Let’s use Fidelity as an example. When we screen for enterprise value, we see that it’s possible to have a negative enterprise value. Which is indeed true – a company’s stock could be worth less than the cash it has on its balance sheet, because the market doesn’t trust the company will do anything profitable with that money. Small biotech companies are often priced this way.

Fidelity’s screener, though, shows some massive companies with negative enterprise value. Many of them are either foreign companies or financial companies. Banks are more complicated to account for because they hold cash but it’s not their own, it’s their customers’ deposits. This isn’t super helpful. That doesn’t invalidate the screener as a whole, but it’s important to realize. Specific criteria can be defined differently, and while Fidelity’s screener is wrong, you have to understand how it’s wrong if you want to still use it.

Data relevance

Even more important is that the data will be based on the company’s last quarterly or annual report. The recent past is important, but stocks are valued on what they are expected to do in the future. Analysts estimates are a small piece of this, but if a company is transforming itself, or if it bought another company, or if we had a global pandemic that made things really weird for a couple years and the economy is still adjusting, the screener won’t exactly show that. You have to apply common sense, and you have to understand you may miss out on things that the screener hasn’t picked up on yet.

Static approach

Piggybacking on the last point, a screener is static. It is backwards looking for the most part, and it doesn’t easily adapt to market circumstances. It’s tough to unearth fresh ideas – there are thousands of investors picking over the most popular screens. So a simple ‘cheap, growing, and small’ screen like this might not produce interesting companies.

Fishing in the right pond

My dad told me a story once*. He was a college graduate in Soviet Moscow, as a Jew from a city in another Soviet Republic, Kharkov Ukraine, he needed a passport to stay in Moscow. The way to acquire a passport? Marry a woman from Moscow.

“I only dated women from Moscow,” he told me.

My mom, indeed, was such a woman.

That’s a bit of a silly example, but the principle of fishing in the right pond makes sense in the stock market. If you’re trying to find the right stocks from the stock market out of the thousands out there, it’s best to save yourself time and not look at the ones that would never suit you. A screener is a way to weed out the bad fits so that your researching time can be more productive. It’s not perfect, and it’s no more than a starting point, but in the market, a good starting point can be worth a lot. And with the time you save, maybe you can dive back into a newspaper or two, another worthwhile investment.

Subscribe for more posts from How to Buy Stocks

Our next post will detail how to find stocks using other people’s ideas. Meanwhile, catch up on how to find stocks Peter Lynch style, and on our full course on how to buy stocks.

*He told me this because he thought my girlfriend at the time was too old for me. She is now my wife and he loves her. There are limits to the “right pond” approach.

2 responses to “How to Use Stock Screeners to Find Stocks”

[…] For our next post in how to buy stocks, we’re going to talk about how to use stock screeners to find stocks. […]

[…] There’s the Peter Lynch style of buy what you know, using your everyday insights. There’s screeners, which allow you to filter through the world of stocks to get to the criteria you like. And […]