Today we’re going to talk about how I came to buy Steelcase shares. But before that, let me explain why.

I’m a believer in learning by doing. That applies to investing as well. There’s a phrase or an idea I’ve heard in investing: your tuition fees for learning how to invest come in the mistakes you make. You lose money on an investment or trade, learn from it, and don’t repeat the mistake in the future – at least, that’s the hope.

At the same time, it’s better to learn from other people’s mistakes and successes. You can save some of your money, or at least you can have an idea of what a success or failure might look like.

I’m going to publish a few posts or videos that offer examples of stocks I’ve bought and how they are turning out or have turned out. And then I’ll use examples from famous investors, or from groups of people. The idea is never to poke fun or mock anyone except myself. It is to learn and illustrate.

I’ll start with one of my newest ideas, because the process is freshest in my mind. While it is working so far, it comes based in an idea that in the end, didn’t make me much money. There are unexpected events that break in both directions. There are outstanding questions for the future. But I hope it can illustrate a lot of what we’ve talked about so far.

Why Steelcase?

The Back Story

I bought Steelcase shares in May 2023, but my journey to that decision starts in the summer of 2014.

I had just read Joel Greenblatt’s You Can Be A Stock Market Genius. The book is famous for detailing special situations that investors can look for as investing ideas. Spin-offs is the best known example, i.e. a situation where a company spins off a unit or part of its business to investors.

This led me to Kimball International (KBAL), a furniture company and an electronics manufacturer.

Kimball was splitting in two, with its electronics manufacturer becoming an independent company, Kimball Electronics. This worked out well because the companies didn’t really overlap, and because this was a small company so not many people followed the situation. Kimball Electronics traded as low as $5.19/share its first day, though it would close at $10 in two days and just about never trade below there again. I couldn’t believe my eyes or my own analysis, so I made some money but not as much as I should on this.

Anyway, I ended up owning the furniture company shares for much longer. The shares got cheap, I bought them in December 2014, and over the next five years, the company did really well. Kimball shares grew about 20% a year for those five years, and it paid about a 2% dividend.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Which brought us to the pandemic came. Few industries were more severely affected than office furniture. Offices closed for a long time, and to this day people haven’t filled offices the way they were before 2020.

I got lucky, though. In times of industry pain, competitors often try to bulk up to survive. Which meant, in this case, that HNI bought Kimball. I sold shares as soon as the news was announced, and ended up marginally ahead for nearly 9 years of waiting. Not ideal.

For all that, I thought office furniture was still an interesting place to look. I believed (and believe) that more people will be in offices in 2026 than 2022. These companies were the rare ones to have not recovered as a stock nor as a business. Legitimate cheap stocks that I could understand were hard to find, and so I wanted to dig in.

Zeroing in on Steelcase

With HNI buying KBAL, there were three publicly traded office furniture companies in the U.S.: HNI, MillerKnoll, and Steelcase.

I liked Steelcase most out of them because a) it was cheaper, and b) it had the least going on. HNI would have to integrate KBAL, a big acquisition; it has already decided to get rid of Poppin, KBAL’s big swing acquisition during the pandemic. MillerKnoll is the combination of Herman Miller and Knoll. The negotiation for that deal was contentious, and MLKN’s CEO made bad headlines, suggesting underlying stress. Steelcase has made small acquisitions, but for the most part, its problems are its own.

In studying Steelcase, I had to figure out what was going wrong, so I could understand what might go right. The stock chart suggested a steady grind lower, with September 2022 having a big drop. In its earnings that quarter, the company missed their estimates, announced layoffs, and cut their dividend. Investors especially hate it when a company cuts dividends. The subtext to all of this was that any quick snapback recovery to pre-COVID sales and profit levels was unlikely.

What I studied to get up to speed

The Steelcase story isn’t very complex, but what I could glean from different sources is illustrative. We can look at the full list of where to find info as a reference.

The company’s filings (its most recent 10-K, for example) are still the core of my research. They show that Steelcase remained profitable in the pandemic, produced free cash flow in two of three years – in the third, cash flow was negative due to an inventory build-up – and that its debt wasn’t too bad. Its proxy form shows that the company has a legacy family ownership, making a sale less likely.

Its investor day presentation shows management’s expectations – reasonable but positive – and research on the state of the office. Earnings transcripts suggested analysts were most focused on margins rather than revenue, perhaps because a company can do more about margins.

And the company’s stock chart and filings show that, since it came public during the dot.com boom, Steelcase has been a poor investment.

I went further afield. Competitors’ merger documents shed light on how peers are expecting to grow in the years ahead. I learned that its private competitor, Haworth, set a revenue record in 2022, so things weren’t bad for everyone. A book about Bassett Furniture, a home furniture maker, painted a grim picture for the industry. I could have reached out at some point to talk to people who worked at these firms – many are based in the Midwest, so I don’t have to reach far to find people – but have not done so yet.

How the picture looked: The Company

I laid out four things I look for in a company I want to buy shares in. From all that research, here’s how I squared Steelcase:

Revenue growth: Not yet

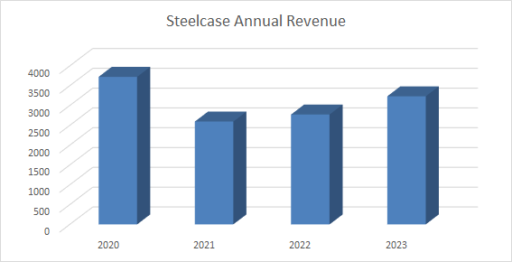

Office furniture companies struggled during the pandemic, and then during the inflationary rebound, and are not back to pre-pandemic levels, for the most part.

Steelcase is among these companies. Its revenue in its 2023 (ending in February 2023) was 13% below its revenue for the year ending February 2020.

When I first studied Steelcase, the company said it expected ‘modest’ organic revenue growth this year. Since, it has revised that expectation to a modest decline. No growth this year.

My hunch, intuition, and somewhat supported belief is that we will be working more in offices in 2026 than 2022. If that’s the case, whether due to replenishment or reorganization, companies will need to buy more furniture. I think there’s a plausible path to get back to 2019 revenue levels by then.

The company, for its part, is targeting 5-7% growth over the next 4-5 years, after this year’s speed bump. That sounds optimistic to me, but it would be really great for the stock if it happens.

Understanding the business

Having owned Kimball shares for nearly 9 years, I had a background with office furniture. This is also not a very hard to understand business. I don’t need to know the nuances of manufacturing processes or designs. Understanding how companies source materials and where their costs are, how they sell products, and what drives success or failure is not so hard.

Steelcase is bigger than Kimball, and more international, so that adds some nuance. It also sells a lot through projects to big corporations, which I have to watch out for. But this was an easy box to check.

Control of its own destiny: a partial yes

Control of its own destiny is a must for a business I want to own. Steelcase has control over its financial destiny. Its debt is not very large, has an interest rate under 6%, and is due in 2029. It will be a long time until that is a major problem.

Steelcase also produced free cash flow in their 2023, so it is not as if it is burning cash. Over the three years of the pandemic, Steelcase was profitable each year, and positive free cash flow in two of them. In the third, as I mentioned above, a lot of cash went into inventory, which isn’t a problem as long as you eventually sell the inventory at full price.

Operational control is more fleeting. The industry depends on corporations in other fields returning to the office. Steelcase can counsel those companies, but can’t do much to generate demand.

At the same time, I liked that Steelcase didn’t have to worry about a major merger. And, seeing that Haworth was doing well, I had the sense that Steelcase could be doing better. Whether or not that falls under its control is unclear, but at least there was room for improvement.

Efficiency: A return to form needed

That room for improvement is especially evident in Steelcase’s efficiency. The company wasn’t much less efficient than its competitors. But its gross margins dropped a lot in 2023 vs. pre-pandemic levels. And so did its operating margins. Basically, if Steelcase could figure out margins, half the problem would be solved.

There’s a saying I like, that bad is good, because you can turn bad into better. In other words, in investing we get paid when situations improve. If Steelcase could return its gross margins to 32.6% (from 28.5%) last year, that would make a huge difference on the shares.

Meanwhile, the company has not historically needed to spend a lot on capital expenditures, meaning it can produce real free cash flow if things get better.

How the picture looked: The Stock

The story for the stock is a little more straightforward. Steelcase used to make more than $1/share in earnings, and was trading at $7.75 or so when I started buying shares. If it could get back to $1, the PE of 7-8 wouldn’t stick, and shares would go much higher.

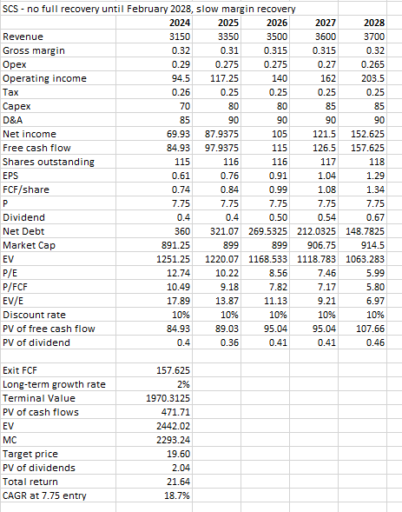

I developed a discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation model to assess absolute valuation. Starting with the company’s projections from its investor day, I lowered the growth rate and margin expectations. I then ran four different models (the last being the company’s projections). In each case, the fair value was more than 50% higher than the current share price, and in some cases much higher. Here’s one model:

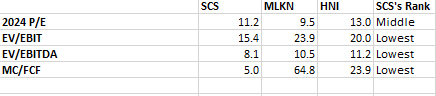

The relative valuation was also reasonable. On the one hand, Steelcase traded at less than the S&P 500 on forward estimates. It also traded at less than its historic multiple, in part because the market doubted it would grow normally.

On the other hand, its peers also traded cheaply, but Steelcase was generally cheaper. I don’t have the May numbers anymore, but this is how it looks in October:

Understanding the disconnect was also fairly straightforward. The market – justifiably – had low expectations for office furniture. Even as I bought shares, the New York Times published stories about office furniture ruin porn and why we won’t go back to a 5-day office week.

Not that those articles are wrong. Just that, I don’t need things to go back to 2019 for Steelcase to have success. In the above model, the company never reaches 2019 sales, even after it has hiked prices. And the stock is still worth nearly 180% more, including dividends, I argue.

The risk/reward is the last piece of the puzzle. I felt confident Steelcase would not go bankrupt, given the cash flow and balance sheet statements. Could it stay stuck at $.30/share in earnings? Yes, plausibly. At that level, the shares might drop to a 12x earnings multiple – way less than the market, but maybe factoring in some non-GAAP adjustments or otherwise leaving a scintilla of hope. That would be $3.6, 54% lower. Vs. 180% upside, say. The risk reward is favorable, especially as I think upside is more likely than downside.

What happened after I bought?

Once I decided to buy Steelcase stock, I felt all the usual emotions. I bought 50% of my position on May 12 and May 15th, around $7.6 a share. The shares plunged the next day to about $6.8. I had no idea why, so I bought some more shares, and waited till the end of the month to fill out that next 25% of my position. I then decided to wait for earnings.

Steelcase has reported earnings twice in the past five months. The first time, it reported B- or B level results – beating estimates, maintaining guidance, and showing that no worse was to come. The second time, it reported B+ or A- results – beating estimates and raising earnings guidance, while dropping revenue guidance. Shares rose a little after the first earnings, drifted higher, and then jumped on the second earnings.

It’s too early to say whether this investment is a good one or not. My fundamental premise is office furniture sales will get better, and there are no signs of that yet. I did think that they couldn’t get much worse, and so far that’s played out with the stock. But 5 months is hardly time to evaluate a medium to long-term investment.

And, I want to be careful to not be fooled into thinking Steelcase is an amazing business. I’ve learned enough to see how tough furniture is. I still think the stock should be worth more, and that it will go higher over time, but this is not like holding shares of, say, Costco forever.

A constant decision

The point of sharing all this is not to say you should buy Steelcase shares. Or that I was right for buying Steelcase. Or that this is a perfect investment process.

I just wanted to translate everything we’ve talked about so far into practice. I may not have gone through every step that I preached, but this was a fairly representative investment research process for me. Ignore the math or the calculations, and see if that makes sense to you from a ‘how did we get from A to B?” perspective.

I hope that it did. But in case it didn’t, I’ll go over a few more examples, including mistakes I’ve made of both commission and omission. Stay tuned for more.