We’ve learned how to start investing. It’s time to talk about buying stocks. For the Short Investing Guide on how to buy stocks, we’re going to cover the following topics:

- What to know about finding a stock to buy

- What type of investor are you?

- How to find a stock

- How to evaluate a stock and a business

- What to review when you are trying to understand a company

- What I look for in a company

- Mechanics of buying a stock

- Real examples

These topics entail the actual searching for, analyzing, and buying a stock. But before we do anything, we need to understand a few basics.

Subscribe to get each new post of this course in your inbox

In this article, let’s talk about what you need to understand about the concept of buying a stock.

What is a stock?

A company can raise money in two ways – borrowing money, or debt, and selling equity or ownership. Debt allows a company to maintain ownership in their business, as long as they can pay off the debt. If they don’t, their lenders can eventually take control of the company. Debt is riskier in this way.

Equity doesn’t come with the obligation to pay anything back, but it does give away a part of a company*.

*If a company is ‘self-funding’, it means the founders or owners own 100% of the equity.

When a company wants to raise money without taking on debt, either in the start-up phase or through their initial public offering (IPO), they sell equity. Equity and stock are interchangeable. When we buy a stock on the stock market, we buy it in units that are called shares. For example, in the portfolios I manage, I own shares in Progressive Corporation, a leading car insurance company in the U.S. – think Flo from the commercials.

What does owning shares give me?

When I own shares of Progressive, I own a piece of the business. It’s a tiny piece of the business*. I can’t march into the Progressive boardroom and demand they change their strategy. But I own part of the business, and a right to their future earnings. Not in a literal sense where I can say ‘hey, Progressive, give me X dollars’. But in practice, if Progressive pays a dividend, all shareholders** receive the same dividend per share. Whether it’s the CEO, the hedge funds who own it, or little old me, we get the same thing.

* .000004%, if I got my math right, give or take a couple decimal points.

** There are two classes of stock – common stock and preferred stock. We may touch on preferred stock much later on, but in the U.S. the stocks you hear about and that we will talk about 99% of the time are common stocks. This is not always the same in other countries – in Germany, for example, preferred stocks are much more widely traded than in the U.S.

Dividends and share buybacks are the most typical direct way for companies to pay their shareholders. As shareholders, we are not just left waiting around for dividends, however. Stocks will rise and fall based on expectations for future earnings. If Progressive is expected to make more money in the next five years than was expected before, its shares will go higher. If it is expected to or proves to make less than previously expected, its shares will go lower.

Why do we buy stocks?

The most typical reason* to buy a stock, literally, is because you think its price will go higher.

* There is a strategy that just buys stocks for the dividends, called dividend investing. Some people are happy with that, and it can work for them. We’ll address that later.

Why would it go higher? Over the longer term, the price of the shares aligns with the profits the company will make, or the profits the market* – all the people out there who are buying stocks and making guesses about the future – expects the company to make.

* You’ll hear “the market” as if it’s an abstract thing. Think of it instead as the hive mind of millions of investors in the world buying and selling stocks, causing the share prices to change daily. Benjamin Graham had a Mr. Market metaphor that we’ll cover at some point.

In the shorter term, that guessing game causes the sentiment about a company’s prospects to swing wildly.

Voting machine vs. weighing machine

There’s a famous phrase that captures this, that has been attributed to Benjamin Graham. Graham is considered the founder of modern value investing, and was one of Warren Buffett’s greatest mentors.

In the short term, the stock market is a voting machine, and in the long term it’s a weighing machine.

Benjamin Graham, purportedly*

*I have not seen the direct quote in his two most famous books. The principle is fairly attributed to him.

Meaning: in the short term the participants in the market vote for what they think will happen, and in the long term, the results bear out, and the companies that perform best will see their stocks go higher.

When we buy stocks, we are often buying at a point where the voting is ‘wrong’, in comparison with the company’s longer-term prospects. Of course, that’s always going to be just our opinion, but that’s why I buy a stock – I think the corresponding company can grow its longer-term prospects more than the market thinks the company can grow its longer-term prospects. In other words, I’m trying to buy a stock for less than its value, so that when the stock’s price rises to match its value, I will be rewarded with a more valuable holding.

Two common misconceptions about stocks

At this point I want to call out two potential pitfalls for new investors:

1. Price ≠ value.

When we talk about price, we talk about what the share price is for a company, what its market capitalization is – the total value of its equity – and what its enterprise value is – the company’s full value when you account for its debt or cash position.

Value is subjective, but that is what the company ‘should be worth’. That is in the eye of the beholder, of course, and our job is to figure out what the market will value over time. But value is different from price.

To use a Buffett saying, “price is what you pay, value is what you get” (slide). Or to go back to the earlier phrase, the market votes on price, but eventually the value is what gets weighed.

2. Share price ≠ price on its own.

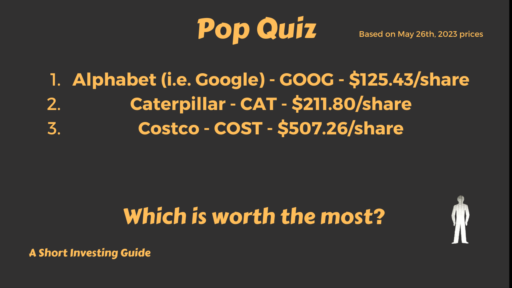

Here’s a pop quiz: which stock is worth more as of May 26th?

The answer: Google, which had a market capitalization of $1.6 trillion at that date. Costco had a market cap of $225 billion, and Caterpillar had a market cap of $109 billion.

Follow up question: which is the most expensive?

Answer – we don’t know from the information given. This is a much trickier question. Expensive can mean literally ‘how much are you paying for each $ of profit the company makes’, which we can answer mathematically.

It can also mean ‘how much are you paying for each $ of future profit’. How much we want to pay for a certain business can depend on how ‘good’ we think the business is, which gets subjective.

You don’t need to know those answers yet. Just be careful not to confuse share price with price, and be careful when someone says something is expensive or cheap. Ask them (or yourself) why that is? On what basis is the stock cheap?

So why would I buy a specific stock?

We’ve talked about how price does not equal value, and how the market votes in the short term and weighs in the long term. When I buy a specific stock, I’m buying because I think that the stock weighs more than other people are voting on it weighing.

Another way I’d put it: as a rule of thumb I invest either because I think that the company is making enough money now and it won’t get worse, while the market thinks it will get worse, or I invest because I think things will get better, and the market doesn’t. I’m looking for a story that will show up in the numbers before they show up in the numbers, at which point other investors will understand that it’s in the numbers.

Get more of A Short Investing Guide in your inbox

When I invest, I’m trying to figure out what I think that the market doesn’t know yet. We’re not going to obsess about it, because it can be hard to pin down that ‘edge’ or ‘variant view’. But you should at least have an ‘investing thesis’ when you buy a stock that makes the case the market is missing something.

When I bought Progressive shares in the fall of 2019, I thought the company traded too cheaply compared to its earnings for how good a company it was. So far, the stock has outperformed the S&P 500 in the 3.5 years, but that doesn’t on its own mean this was a good pick. But that’s a topic for another time.

In our next post, we will talk about the most relevant investing styles to consider before we start buying stocks. Stay tuned for that.

Disclosure: As of this publishing in June 2023, I own shares of Progressive Corporation – PGR – in the accounts I manage, including my own. I also own shares of Berkshire Hathaway – BRK.B, Warren Buffett’s company. I don’t plan to make any change to my position in the coming months, but changes may happen depending on market circumstances. Nothing on here is specific investment advice.